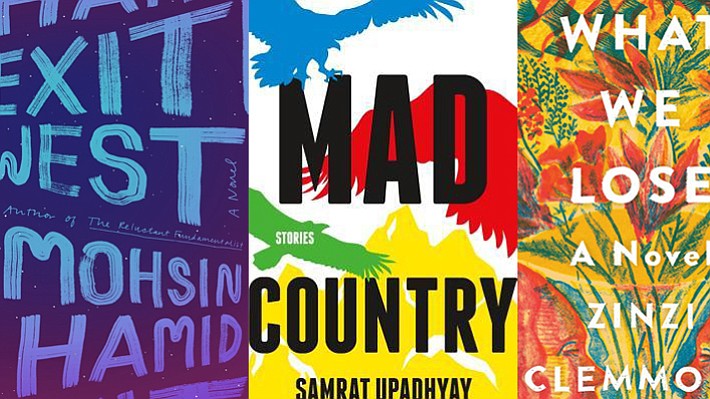

Samrat Upadhyay’s latest book Mad Country is in excellent company. Alongside Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West, Jesmyn Ward’s Sing Unburied Sing, Zinzi Clemmons’ What We Lose, and Lesley Nneka Arimah’s What It Means When A Man Falls From The Sky, Upadhyay’s Mad Country has been a finalist for this years’ Aspen Words Literary Prize.

Upadhyay has not only been a rising star in international literary scene, but also a source of inspiration for many Nepali writers like me. I’m honored and thrilled to feature him on my blog.

(Like featured segment? Subscribe here so that you don’t miss out on future posts. Check out current promotion, exclusive only for subscribers!)

For those who do not know you yet, can you tell a little about yourself—don’t be shy!

I grew up in Nepal but came to the US in 1984. I was always interested in literature and writing and was a voracious reader when I was young. There was no television in Nepal in the early 80s, so reading, along with radio and cinema, was a major source of entertainment. At that time I was not a discerning reader. I used to read anything I could get my hands on: serious Hindi literature by Amrita Pritam and Premchand; detective novels in Nepali with weird protagonists; lurid Hindi crime magazines; and commercial novelists such as James Hadley Chase and Harold Robbins as well as heavyweights such as Charles Dickens. I am glad that I was not picky at that time because it allowed me to absorb everything and develop my own literary tastes. I was also a big fan of Hindi movies, and know almost all the songs from that era.

I read that you came to the US as a Business student. How did you become a writer?

I was a writer before I came to the US. I wrote in both Nepali and English until my teen years. I was the editor of my school magazine. I even had a crappy poem published in the Friday Supplement of the Rising Nepal in my mid-teens. But it was being in the US that allowed me to explore my true interests, even though I had come here initially thinking that I’d study business (because I didn’t think you could really study literature and writing for a career). I didn’t write much during my undergraduate years but during my graduate work at Ohio University I encountered an influential teacher, Eve Shelnutt. And there were other teachers later who were extremely important in my growth: Michael Bugeja, Paul Lyons, Robbie Shapard, Ian MacMillan. I started writing extremely seriously when, after a couple of years in Nepal, I returned to the US for my Ph.D.

Nepali literature has a rich history, yet in my experience writing is viewed as a mere hobby than a career in Nepali society. What has your experience been like? Have you found it being different for aspiring American writers?

It’s complex. In Nepal, it’s extremely difficult to have a career solely through writing. The publishing industry has shown good growth in the last decade, but it’s hard to make money through writing. In the US, it is possible to make money through writing, but for that one has be a commercially successful writer, which many can’t claim to be. That’s why you see many American literary writers finding refuge in academia, where teaching becomes their main source of income. Even my students, all of whom are aspiring writers, aren’t under the illusion that the commercial success of their writing is guaranteed. Many of them enter publishing or teaching or technical writing other such careers as they pursue their writing. But I think in Nepal too you’ll find many writers in other professions for whom writing is their passion, not merely a hobby.

While some writers plan their plots and characters, others have more fluid approaches. What is your writing process like?

I have a more fluid approach. I don’t like being restricted through pre-planning. I also don’t want to lose the pleasure of discovering my material as I write. To me, that’s the whole joy of writing: not knowing where the story might go, what a character might do. I not only have this open approach to writing my short stories but also my novels.

As a writer who writes in his non-native language, what challenges did you have to overcome?

Although English is not my native tongue, it became my first language by the time I was in my teens, partly through education and partly through my reading habits. The challenges in English for me have less to do with any sense of “mastery” over the language (in fact, during my first semester in the US in 1984, my philosophy professor commented that I wrote much better than most of his students who claimed English as their native tongue) than with translating the physical and emotional landscape of Nepal and being faithful to that fictional truth–while simultaneously attempting to be original and bold in my art.

I read Arresting God in Kathmandu a few years ago. What comes to mind as I think about the short story collection is wanting to know what happened next. The Kathmandu you portrayed was reminiscent of the city I grew-up in, characters were lively and authentic, I loved reading each story but was disappointed when they ended too soon. Could some of the stories have been expanded more into a novella or a novel length? How do you decide what to pursue further and what to keep short?

I think all stories can be expanded that way. My first novel, The Guru of Love, was actually an expansion of a lousy short story I’d written a while ago. In my mind, my stories, in Arresting God in Kathmandu and in other collections, are as complete as they can be–I haven’t cut them short. The readers’ experience can be entirely different, of course.

Tell us a little about Mad Country—what can readers look forward to when they pick it up?

It’s my most innovative book to date, both in form and content. I think readers used to my earlier work will find it very different.

https://www.amazon.com/Mad-Country-Samrat-Upadhyay/dp/1616957964

Who are your three favorite writers and why?

My normal list has more than three writers, but for today, let me list these three:

William Trevor–for his ability to quickly focus on the inner lives of his characters

Cormac McCarthy–for his language and his stark, brual landscapes

Rohinton Mistry–for his panoramic view of the Indian society and his attention to details.

When you are not writing, what’s your favorite way to spend time?

Reading and teaching and traveling and watching good shows and movies.

What is the best way to connect with you?

By reading my books.

Thank you Samrat dai for talking to us today! I’m looking forward to reading Mad Country and I wish you every success with this book and your future releases.

If you have comments and suggestions about featured segment, please let us know below. If there is an author, writer, musician or artist you would like us to feature, do let us know as well.

Liked this segment? Don’t miss any updates, subscribe here.

We’ll be back again with another featured artist soon. Until then, keep reading and writing. I’ll leave you with this quote to muse on.

“There is only one difference between a madman and me. The madman thinks he’s sane. I know I’m mad.” ~ Salvador Dali